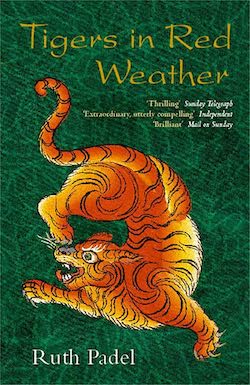

Published by Little, Brown / Abacus, 2005, 448 pages

This is a travel book with a difference: it is also a call for the conservation of wildlife ⎯ tigers in particular ⎯ and wild spaces.

Ruth Padel is a single mother living in London. When a five-year affair with a married man breaks up, she is devastated. She initially romanticizes tigers as solitary survivors, something she can identify with. Then a chance trip to Kerala, India, brings her close to the real animal, and her interest in tigers is kindled.

Padel journeys to all the places where tigers live in the wild: India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan for the Bengal tiger; Russia, South Korea and China for the Amur or Siberian tiger; and Indonesia for the Sumatran tiger. And she goes to the places where the Javanese and Bali tigers ⎯ now extinct ⎯ used to roam.

And everywhere she goes, she finds stories of deforestation, poaching and corrupt officials. Hope is thin on the ground, but is found in the work of dedicated people all over the region, determined to save the tiger and the wilderness.

Tigers are important to the forest ecosystem: if the tiger is healthy, the forest is healthy. It means prey are plentiful, and they in turn have enough to eat, and so on, all the way down to the insects.

“Any loss disrupts links between predators and prey, flowers and pollinators, fruits and dispersers of seeds. All have to be saved together, even leeches, in the wild. Zoos won’t stop the loss cascade. Losing the way they interact means losing the earth.”

She finds Bhutan ⎯ a small country with an incredibly varied ecosystem ⎯ working hard to preserve its wild species. Like on some of the reserves in India, the Bhutanese government tries to involve villagers living near forests in conservation by providing them with alternative livelihoods that would not include clearing forested areas or killing tigers. In Russia, she visits a Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) field station near Vladivostok.

The dark heart of tiger decimation is China, where the demand for tiger parts as medicine has created a multi-million-dollar industry. The Chinese government has been finally coming to grips with the illegal trade but it still has a long way to go. In China, too, people are fighting to keep the tiger and its habitat alive, as Padel finds when she goes to a tiger reserve in Jilin province in eastern China.

Padel is a poet, and it shows in the ways she writes: in Periyar in the Indian Western Ghats, she takes a boat “in silver mist and saw drowned trees with cormorants on them, and white-breasted kingfishers with dazzling turquoise wings”. She describes sunrise in the Sunderbans, a mangrove forest that stretches from West Bengal to Bangladesh: “Sunrise. Orange eye in blue-veined cloud. A monitor lizard, blush-pink and silver-green, scrutinized water from a branch.”

Interspersed with her description of her journeys are glimpses into the end of her affair and the slow healing that takes place. Normally I would find this diversion irritating, but here, it works.

This book is not an easy read but it is worthwhile. Padel is not particularly athletic ⎯ her daily exercise is walking the dog ⎯ but she gamely skids down near-vertical forests and walks miles through rough terrain in search of something she cares deeply about. She starts out as a city dweller who is taken with the romantic idea of tigers and ends as a tiger expert and an activist for conservation.

This review first appeared on Women on the Road.

Leave a comment