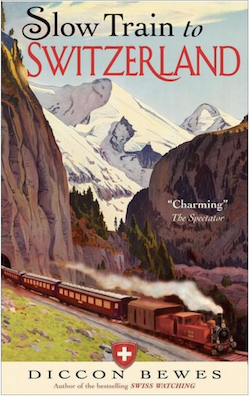

Published by Nicholas Brealey Publishing, 2013, 320 pages

While researching a book on a Switzerland, Diccon Bewes—a Briton who has lived in Switzerland for over eight years—found a reference to a diary written by an English woman, Jemimah Morrell (known as Miss Jemima) who traveled with Thomas Cook’s First Conducted Tour of Switzerland in 1863. He was intrigued.

Found in the post-war rubble in London’s East End, safe in a tin box, the diaries were published as Miss Jemima’s Swiss Journals, and then forgotten. Bewes managed to obtain a copy of the 100th-anniversary edition. The diaries were a time machine, taking him 150 years into the past of a country he knew well. Accompanied by his mother and Miss Jemima’s ghost, he decided to retrace her footsteps, sticking as close as possible to her mode of travel. He would see for himself how much, or little, Switzerland had changed in the last century and a half.

In some ways, the Switzerland Miss Jemima visited was dramatically different from the country today. It was poorer; most people lived off the land and certainly could not afford leisure travel. The Swiss railway routes were limited and service was nowhere near as efficient and extensive it is now. Swiss tourism was in its infancy, and neither Heidi nor milk chocolate existed. But some things have not changed: visitors then, as now, complained about the high prices!

The Swiss journey Thomas Cook organized in 1863 was an attempt to persuade ordinary British people to explore the continent, until then a prerogative of the rich. The birth of middle-class tourism driven by a growing railway network helped make Switzerland wealthy.

Miss Jemima’s group of seven, who called themselves Young United Alpine Club, included four women and three men, including her brother William. These intrepid Victorians traveled by train, carriage, ferry, and often on foot, walking for miles and making modern-day travelers look pampered. Their schedule was grueling: Usually up at 5 am, traveling all day, rushing to briefly explore their destination before bedtime, and off again the next day. Neither trains nor carriages had bathrooms, and I have a special admiration for the women, clambering up narrow paths carved out on mountains in long dresses and corsets—paths that I would find difficult in trousers and good boots.

The book is full of interesting facts. In 1863, Geneva time was five minutes behind Bern but 15 minutes ahead of Paris. This made it challenging for trains to run on time, so Swiss time zones were standardized in 1894.

Bewes reveals many links between Britain and Switzerland: Thomas Cook’s tours started the tourist invasion of the country, English engineers were called to help set up the Swiss railways and—believe it or not—the British invented skiing (on wooden skis)!

I loved the alternating perspectives on Switzerland—Diccon Bewes’s and Ms. Jemimah’s, whose observant and at times mischievous voice often dominated. She describes a downhill descent on a mountain path: “rugged with loose stones which threaten to make mincemeat of our shoe soles. Even the mules are…discarded…. In fact, one mule discarded its rider… to give the animal his due, there was some display of oriental grace in the camel-like kneel with which he preceded his nonchalant roll across the path.”

I have lived in Switzerland for almost 30 years and know a lot of the places Bewes describes – but I hadn’t seen them through these eyes. I will now take this book—and its two knowledgeable guides—with me when I travel in the country. And I would invite you to do the same.

Read my interview with Diccon Bewes.

This review first appeared on Women on the Road.

Leave a comment